Approaching Art

Jim's Musings from Paris March 2024

During the last few months, we’ve visited several powerful art exhibitions. Trying to process or understand the aftermath of seeing these shows brings up the question: How does one experience great art? I awoke suddenly one night last week with the urge to write down two very different, yet critical, moments from my life—as a response.

The first episode occurred at my brother Bob’s wake. His friends from St. Louis called me in California from the hospital right after the accident. They called me even before they called my parents because they knew that Bob and I shared something very special. I immediately phoned my parents in Illinois. They had already been contacted by the hospital staff and knew that Bob had died. We all entered a fog. I don’t know how I made the arrangements to fly to Chicago. Lollie, my girlfriend at the time, and my dear friend Julie, held me up. That damned phone call, that phone call everyone dreads, came shortly after midnight on September 1. In the morning, I found myself alone on a plane. I leaned my head against the window and softly sobbed as we flew over the desert, the Rockies, and the endless fields of grain.

The next few days were a blur, a whirl of activity, as the funeral was planned, relatives arrived, and Bob’s many friends congregated. I remember standing in a line with my Mom and Dad and two brothers, (and a former girlfriend, Alison), receiving people at the funeral home, at the wake. People were offering their sympathy. Grotowski always hated that word—sympathy. He found it maudlin, an easy Hallmark substitute for true compassion. But everyone was doing the best they could in a terrible and tragic situation. We were holding up.

Bob’s high school English teacher approached me. He loved this teacher. She introduced him to The Brothers Karamazov and The Fountainhead. She encouraged his writing and his questioning of the status quo. We had never met. She introduced herself and told me how much Bob had admired me and spoke to her often about me and my work in the theatre. As I opened my mouth to thank her, a howl of anguish from the depths of my being emerged instead. The cry had such force that it pushed the frightened woman back away from me. She was shocked, apologized, excused herself, and quickly disappeared. I was left gasping for air, also shocked, unable to speak. I knew that I had touched something profound, the core of grief, perhaps. It was an experience I would re-visit from time to time when I remembered my brother or experienced other deep losses in my life. I felt it again at the Rothko exhibit here in Paris which we saw last month at the Foundation Louis Vuitton.

When I found myself in front of one of Rothko’s great empty spaces, I again connected with the need to howl, to cover the canvas with my own grief, anguish, love. Rothko’s work compelled me (as great art should) to unplug the inner reservoir and react—actively. My body revealed this truth when it woke me some days later—the memory of Rothko’s fields of color and my own anguish throbbing in my throat.

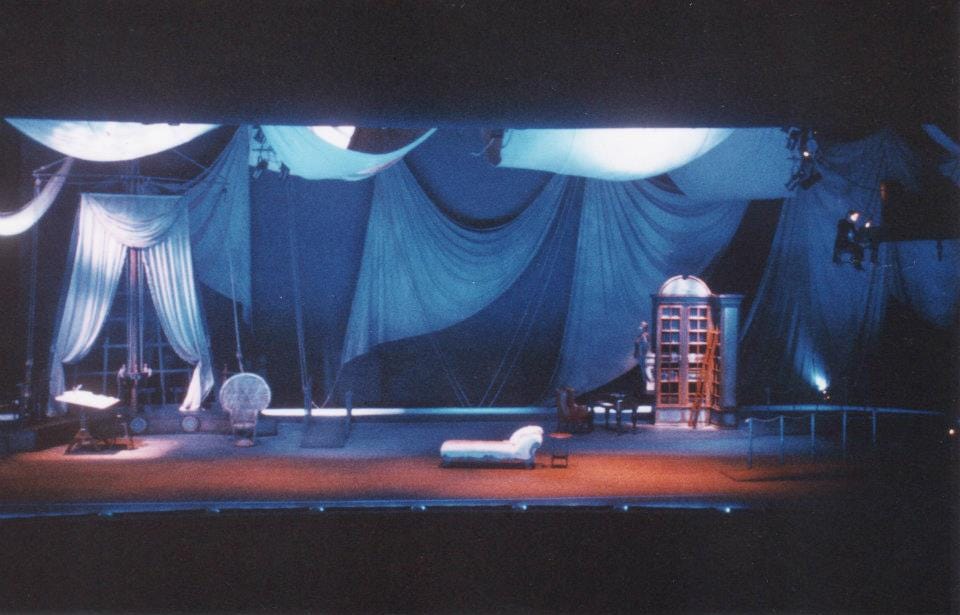

The second episode on my mind when I awoke in the night last week happened seven or eight months after Bob’s funeral. Spring 1985. I had finished directing George Bernard Shaw’s Heartbreak House as my thesis project at UC-Irvine and returned to the Objective Drama work spaces, assisting Grotowski in the daily work. Jairo Cuesta had recently joined the team of Technical Specialists and was leading the participants in exercises to develop the structure for what would become Watching. With Jairo’s arrival, Grotowski knew he could also begin to introduce us novices to what was known in Para-Theatre and Theatre of Sources as The Fire Action.

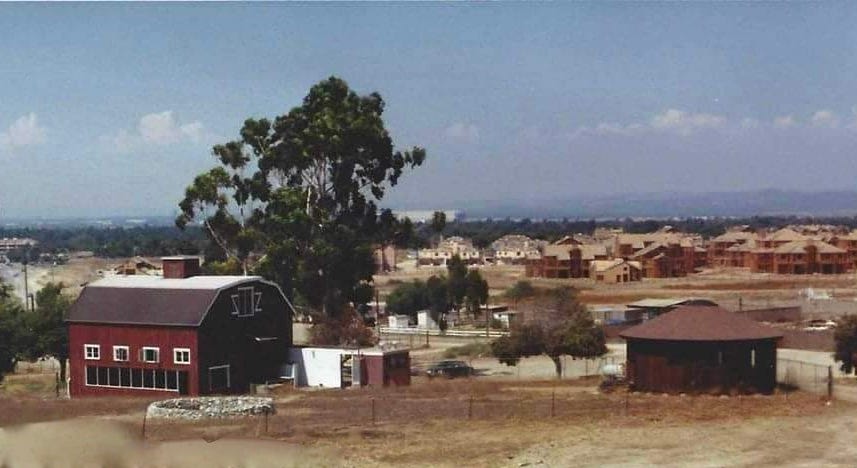

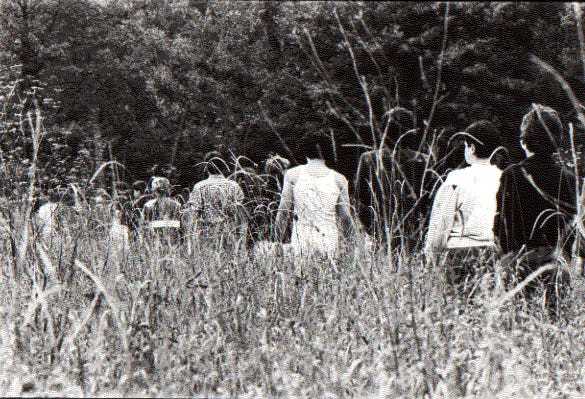

When Grotowski agreed to come to Irvine, he asked that some renovations be made on The Barn, the primary work space and center for his research. He also asked that a yurt be built adjacent to The Barn, as well as a firepit. Imagine convincing university authorities to build a firepit on the outskirts of campus in the middle of a field in Southern California. The fear of wildfires had not yet reached its current peak, but everyone was nervous. If we were going to use the firepit, local fire departments needed to be notified, several extinguishers had to be ready on site, and all of us had to be trained in how to use them to control any errant sparks. After a lot of preparation, which included me looking all over Orange County for a bottle of Haitian rum, Grotowski announced one night that Jairo would lead us in The Fire Action. The parameters of the exercise included: do not behave toward the fire as you have in the past while camping or at a scout outing or sports bonfire; do not warm your hands or other parts of your body at the fire; do not play with sticks in the fire or light things on fire; do not throw things into the fire; treat the fire with respect; only Jairo or Grotowski have the right to put more fuel on the fire; watch Jairo and be guided by his behavior.

Once the fire was burning steadily, all of the participants joined Jairo, spreading out and balancing the space around the firepit. I watched Jairo attentively as he delicately moved towards and away from the fire as if it were a living partner. I looked at the heap of burning brush and let myself subtly react to the colors and crackles of the dancing flames. From deep inside came the impulse to dart and flick, rise and fall. Time stopped. I tried not to force anything. We all moved silently with the fire, sometimes running and then standing still. If one of us began to make noise or move too grandly, Jairo would calmly approach and tamp down the straying sparks. After a long time, Grotowski, who had remained on the periphery of the activity, entered the firepit and began to pour the contents of the bottle of Haitian rum on the blaze. As the fire flared brightly and then died down, I found myself separating from the group. I turned my back on them and the fire and looked up at the full moon. Compelled by something deep at the base of my spine, I went behind the yurt where I could be alone with the moon shining brightly. I stripped off my shirt and began to dance in a rhythmic flow. My spine undulated gracefully, completely out of my control. My moondance lasted several joyous minutes. Once the energy subsided, I gathered my shirt and came around from behind the yurt. The others were already heading back to the barn and I met Grotowski slowly bringing up the rear. Our eyes met. He paused to let me join the line and I knew that everything had changed.

This pivotal episode from my own life experience became present for me once more as I recently wandered through the Chagall Museum in Nice. A joyous freedom overwhelmed me and I felt like I was moondancing again in the Irvine desert. For me, Chagall’s work provides one of the best examples of the power of art to act on one’s whole being—to provoke deeply hidden memories and propel us into fantastic and mythic worlds. When I told him we were going to the Chagall Museum, our friend Mitchell Kahan, former director of the Akron Art Museum, said : “Joyful artists are too few in this world.”

We encountered other forceful (sometimes joyful) art over the past few months:

Jairo wrote last month about Polish director Krystian Lupa’s production of Les Émigrants that we saw at the Odéon—a highly crafted vision, beautifully acted with strong flashes of genius—a four hour meditation on exile, silence, and solitude. The production arrived in Paris steeped in controversy with its opening last June in Geneva having been cancelled due to hostilities between the 80 year old director and the theatre’s technicians. The fear of continuing troubles prompted the Avignon Festival to cancel its sponsorship of the production in the summer. Lupa, steeped in the traditions and habits of a European theatre where the director’s creative process takes precedence over all else, found himself at the forefront of today’s revolution against tyrannical and misogynistic auteurs. The Odéon stepped in to give the production its début and, while certain masterful aspects of the production cannot be denied, the critics remained unconvinced. I don’t think we will be seeing many more auteur works in the theatre in the near future. The end of an era, certainly. We may miss out on some masterpieces, but in return, we may gain a more human, more compassionate art form. It’s a risk I feel is worth taking.

A few weeks ago, we saw a French television documentary , Au bord de la guerre: Ariane Mnouchkine et le Théâtre du Soleil à Kyiv (To the edge of war: Ariane Mnouchkine and Théâtre du Soleil in Kiev). Watching Mnouchkine and her company of actors interact with a group of Ukrainian students in creating theatre études as a response to the war brought the devastation and cruelty of Russia’s agression closer and made it more real, more present, than viewing hours of news footage. This documentary was fascinating and made me feel joyful to call theatre my métier. As I watched, I was also led to recall some of the impressive work we did in New World Performance Lab over these past 30+ years. Maybe we never went to the edge of war, but we often went to “the edge” and that made the work meaningful for many who participated. Thank you to those who stood beside us and held our hands as we looked over the precipice. What an adventure!

In Nice, we came upon the Henri Dauman exhibition, “The Manhattan Darkroom,” at the Musée de la Photographie Charles Nègre. Dauman, a longtime photojournalist for Life and other magazines from the 1960’s, took photos of all the important people and events of the 1960’s and 70’s. These were the pictures I grew up with. I remember going to my grandparent’s house and leafing through their copies of Life, Look, and The Saturday Evening Post. These photos were imprinted indelibly in my memory—the movie stars, the Kennedys, the assassinations and civil rights demonstrations, the hippies and jazz musicians. Meeting the photos again in Nice showed me how much art was always present in my life, despite not coming from an “artsy” family. From the Black Madonna above the altar in the little Polish Catholic church my grandfather helped build at a rural crossroads in Wisconsin that everyone just called Junction to my father’s polka music and all of his “playing jobs;” from my mother’s talent for cooking and baking to my own discovery of the theatre and the thrill of acting and watching live performance—art was all around me.

Yes, we went to the Côte d’Azur, to Nice and several surrounding towns, to find the sun. February 2024 in Paris had fewer sunny days than any other February since they began keeping track of such things—and I needed some sun. So Jairo and I took off to the south of France for about five days. This also gave me the opportunity to check something off my bucket list: Carnival. I’ve never been to a Carnival—like Rio or Venice or Mardi Gras in New Orleans. I don’t think the St. Paul Winter Carnival really counts. Nice hosts the biggest Carnival celebration in France, but it’s very organized, not like I imagine those other carnivals to be. The parades take place within a secured space and the party does not really spill out onto the street. No crowds dancing samba or throwing beads. Lots of mimosas, though, are thrown from the elaborately designed floats. Is it kitschy? Yes. Is it fun? It’s kind of like going to Disneyland (where we had just been a few days earlier) or the Macy’s Thanksgiving Parade or a large State Fair. Was I disappointed? Not at all. It was still Carnival, the city is beautiful, the sea is gorgeous, and we found at least two days of sunshine. We also took in some of Menton’s Citrus Festival which consists of floats and installations made from oranges, lemons, and mandarins. It’s not Chagall, Picasso, or Matisse, but it’s impressive nonetheless.

Important films for me so far this year:

Past Lives

Maestro

Anatomy of a Fall

All of Us Strangers

Le Règne Animal (The Animal Kingdom)

Other things to note this month:

Missak Manouchian, an Armenian genocide survivor who went on to become a French Resistance hero, and his wife were inducted into the Panthéon in February and France enshrined women’s reproductive rights into its constitution this past week. Sometimes this country’s enlightened behavior astounds me—and then someone blows cigarette smoke in my face while walking down the street. That wakes me up. This week we had a visit from my “petite cousine” (that’s cousin once removed, but “petite cousine” is so much sweeter) and she was telling us about how in Minneapolis now cigarette smoke is not much of a problem, but pot smoke is. Apparently, in the states where pot is now legal, wafts of burning grass hover in the air and can cross property lines. Really? What’s your experience of this phenomenon, folks in Minnesota, Illinois, Ohio, California? Let us know.

Oh, one more bit of news: I have left one of my choirs. The commitment to two groups became too much for me with everything else we have going on this spring. And, as you can see, this newsletter is late. I wasn’t feeling like I was giving quality attention to both choirs. So, I’m afraid, you won’t be able to see me perform “Uptown Funk.” Not right now anyway.

Until next time. Approach some art—if you can see it through the cigarette smoke or pot smoke. Depending where you are. À bientot.

Lovely and touching memories. I found Anatomy of a Fall captivating, but I still don't know (or believe) who did it!!! By the way, which choir did you leave?

It was so meaningful reading your post and brought back so many deep memories.

I first met Grot in San Francisco in the 70’s. We ended up doing workshops/gatherings with Ryzard out in the wiles of Marin. I had the honor of chauffeuring Grot around Berkeley and SF before he was offered the space in Irvine. Around that time my son was born and 6 months later he died. I remember I asked Grot “how do I get through this profound Grief.”? His answer ended up leading me to become a psychotherapist and Grief specialist, which I’ve been for the past 30 years. I am also a collage artist.

I enjoyed Zoom connections to Thomas’s work in Italy a year or so ago.

I think I’ve seen little bits of your work on Instagram. Wonderful work.

I loved Grotowski’s description of origin work.

Do keep me on your mailing list or be in touch

Ninette Larson