I’m sorry that the newsletter is so late this month. We wanted to prolong summer a bit, so we took off for Salento, the ancient region in the heel of the Italian boot. Our motives were twofold: to find the sun and some warm water and to meet up with our long-time NWPL collaborator, Debora Totti, whom we had not seen for two years. Both goals were accomplished with delightful results.

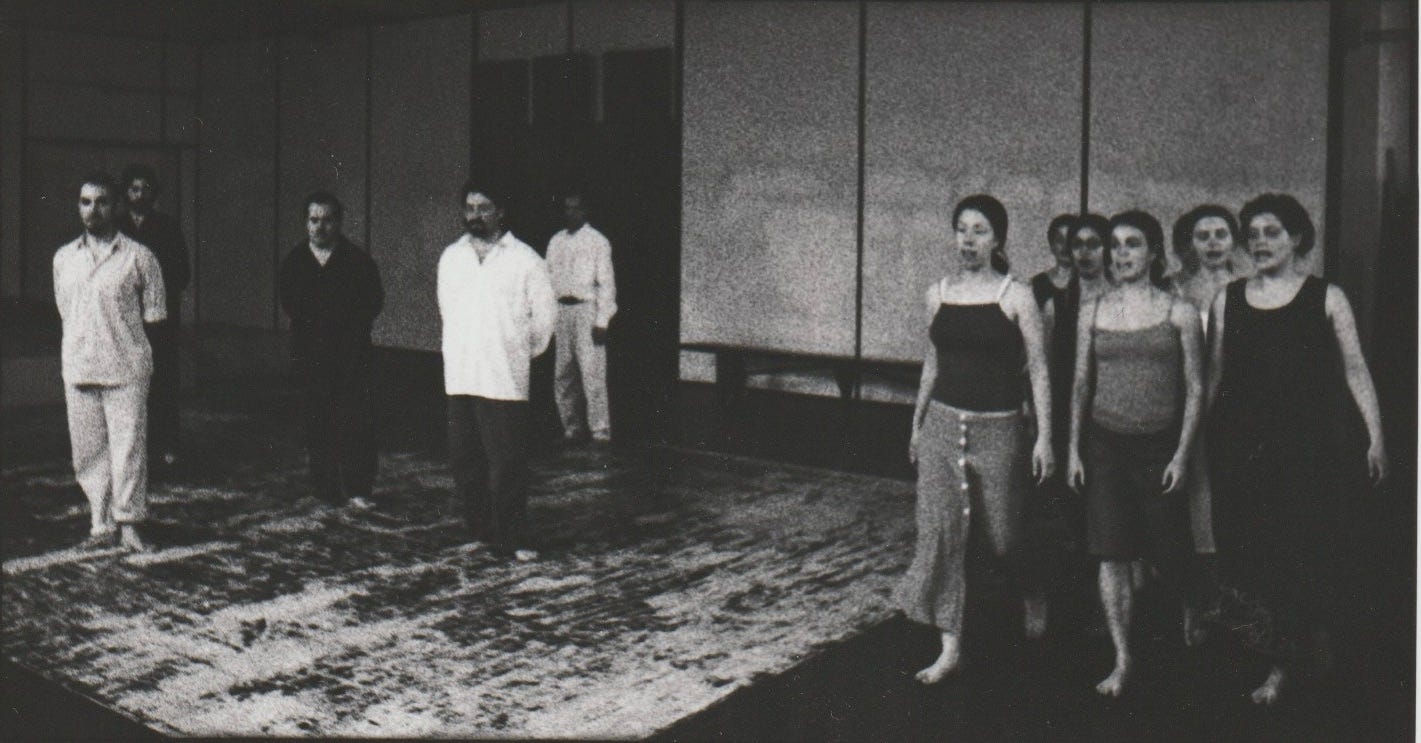

I spent a summer and fall in Salento in 1988, directing a performance for Mediterannea Teatrolaboratorio, a Lecce-based theatre company directed by married couple, Giorgio Di Lecce and Cristina Ria (both of them now deceased). The performance, In Tono Orfico, was a devised piece based on the Orpheus myth, featuring a clarinet player and the indelible Cristina, with text from Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus and fragments from the Dionysian Mysteries, along with other source material. Told from Eurydice’s point of view, the play unfolded as a journey through the desolate landscapes of Salento, the magic and mystery of the region’s women, and its distinctive dance, the pizzica, the local form of tarantella. Salento was the center of the cult of tarantism, thought to be a remnant of the ancient Dionysian cult, and when I was there in 1988, the degenerated traces of the ritual still reverberated feebly throughout the vineyards, olive groves, and small villages. Today, many of those olive trees have been decimated by a quick-spreading disease making the landscape even more desolate and the pizzica has been co-opted and commercialized by the voracious pop culture monster.

Jairo and I returned several times over the years to the baroque city of Lecce to conduct Performance Ecology workshops, invited by Astragali Teatro and its director, Fabio Tolledi, who had stage managed and assisted me in the production of In Tono Orfico. Fabio recently translated Lisa Wolford’s book, Grotowski’s Objective Drama Research (1996), into Italian. This book chronicles my work with Grotowski at UC-Irvine from 1989-1992 and, especially, the formation of New World Performance Laboratory and our early work with Shaker songs in the context of Objective Drama and during the development of the performance, Mother’s Work (1992-1994). I have recently written an article, in collaboration with Alicja Ruczko, which discusses NWPL’s research involving Shaker songs as a tool for vocal work and personal technique. The article was published in Poland1 this summer and will soon appear on Substack.

But back to Salento. On this trip, too, we met with our friends from Astragali and were happy to find them continuously immersed in the work of international theatre exchange and performance creation, and contemplating a move to an old distillery complex in a town outside of Lecce. They gave us a tour of the partially restored, historic buildings and we were in awe of the company’s vision and work ethic. What an undertaking! It made me tired just thinking of all the work they have ahead of them, but excited as well that there are theatre companies still eager to forge ahead with quixotic projects in today’s turbulent world.

However, our main reason for returning to Salento now was to reconnect with Debora Totti, NWPL’s primary actress for more than twenty years. Debora first started working with us in Performance Ecology workshops in Italy in 1996, I believe. After we premiered our production of Woyzeck at Cleveland Public Theatre in Spring 1998, Toby Matthews and Stacey MacFarlane decided to leave the company in order to pursue personal goals. As director, I did not feel ready to stop working on Woyzeck. I believed the production was a real breakthrough for the group and, knowing that Grotowski had faced the departure of company members several times during the years of the Polish Laboratory Theatre and that he replaced those actors with other actors or in other creative ways, I decided to seek two actors that I could work into the already structured montage. I found the answer to my dilemma in Debora and the young Italian actor, Salvatore Motta. Intrepidly, I asked each of them if they would consider coming to Akron to join Jairo and Terence Cranendonk in the work on Woyzeck. Neither of them spoke English very well and we had nothing to offer them except food and housing, but they both agreed. In 1998, it was much easier to arrange long-stay research visas through The University of Akron and Debora and Salvo arrived in October to begin rehearsals.

The work was intensive, broken only by an even more intensive period of work over Christmas, when six other young artists from Italy and Colombia joined Jairo, Terence, Debora, and Salvo to develop a new performance structure for the Shaker songs. Everyone stayed in our duplex apartment on Jefferson Avenue in Akron. We feasted Christmas and New Year’s Eve together and were deeply engaged in open rehearsals when we received word that our mentor, Jerzy Grotowski, had died in Pontedera, Italy. It was a sad coda to a very creative project, Essential Demonstrations, that, unfortunately, we were not able to continue.

We did continue the work on Woyzeck, though, and Debora and Salvo did more than just replicate the performances of Stacey and Toby. They each brought their own personal gifts to the roles and we were able to alter the performance in significant ways. Both versions of the performance are precious to me for different reasons and I can’t say that one is better than the other, but the second version took on a very strong life of its own, which served us well as we toured it to Italy, Bulgaria, and Poland in the summer of 1999. The last performance of Woyzeck occurred at UC-Irvine that autumn at a special conference honoring Grotowski.

Debora gained confidence throughout the process, singing Shape Note songs and acting in a language not her own. She constructed a ferocious, yet sensitive, Marie, full of contradictions and extremely vulnerable. Her strength as a performer is that she brings her total self to each rehearsal—nothing is ever marked or phoned in. She knows how to prepare for what needs to be done and then joyously burns through everything, yet always serving her partners. Debora is the epitome of Antonin Artaud’s image of the actor from his groundbreaking book, The Theatre and Its Double: “If there is still one hellish, truly accursed thing in our time, it is our artistic dallying with forms, instead of being like victims burnt at the stake, signaling through the flames.” We’ve often had to sweep up the ashes after a rehearsal or performance.

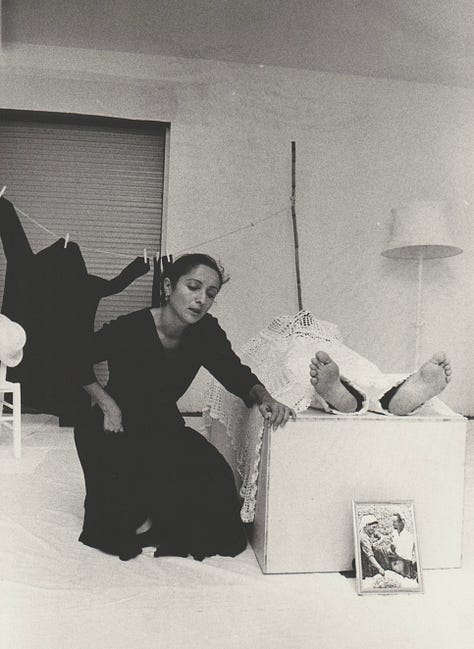

Debora was already an accomplished actor with vast experience before she met Jairo and me. She had worked with several Italian companies and prominent directors, studied in India, practiced Butoh, and was a member of TeatroNatura, under the direction of our dear friend, Sista Bramini.

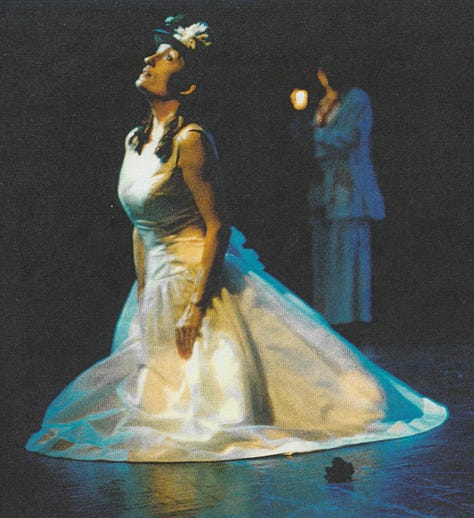

Debora stayed in Akron, falling in love and marrying Terence Cranendonk, and raising a beautiful family. All the while she continued to make herself indispensable to NWPL’s research and performances. She created unforgettable roles, sang a concert with Jairo Cuesta, and developed three virtuosic, solo performances: La Signora, Medea, and Don’t You Weep. I can’t choose a favorite performance of hers. I have strong memories of them all—her drug addled Ophelia in Hametmachine; her strong, savage, narrative voice in Electra; a Marlene Dietrich inspired Columbine in Love in the Time of Lunatics; a ghost-like presence in Frankenstein; the essential third part of the triangle in Gilgamesh, dancing intimately with the two men or running triumphantly around the space to liberate herself from their domination; her dynamic versatility in Orlando, playing everything from Queen Elizabeth I to a Russian sailor; the immigrant anchor of Industrial Valley; and a crazy comic in Don Quijote, playing monkeys, donkeys, maids, and prostitutes with equal aplomb.

Thank you, Debora, for enriching our lives with your vitality and creativity. Thank you for the many years of rehearsals where you were always willing to dig deeper and peel away the superfluous. Thank you for your wisdom and your honesty. I look forward to continuing the journey in other contexts as the curtain rises on our third acts. Remember: Shakespeare’s plays have five acts—so we still have a ways to go.

James Slowiak: Pieśni oświecenia i zjednoczenia. Badania performatywne tradycyjnych pieśni szejkersów realizowane przez New World Perfomance Lab, tłumaczenie Katarzyna Dudzińska, s. 291-308 published in Coś, co jest bardziej mną niż ja”. Prace ofiarowane prof. Leszkowi Kolankiewiczowi, redakcja Marcin Bogucki, Agata Chałupnik, Zofia Dworakowska, Zuzanna Kann-Skorupska, Agata Łuksza, Instytut im. Jerzego Grotowskiego, Instytut Teatralny im. Zbigniewa Raszewskiego, Uniwersytet Warszawski, Wrocław - Warszawa 2024

Having witnessed a good number of Debora's performances over the years, your tribute brought back so many memories! Thank you!