Songs of Illumination and Union

New World Performance Lab's Performative Research of Songs from the Shaker Tradition by James Slowiak with Alicja Ruczko

While I’m working on the October newsletter, I thought I would publish an article I wrote recently with the help of Alicja Ruzcko, which summarizes NWPL’s research on Shaker songs from 1989 until 2003. The article has been published in Polish—but here is the English version. The article may appear truncated in your email. If so, there should be a link you can click to see the entire article.

SONGS OF ILLUMINATION AND UNION:

New World Performance Lab’s Performative Research of Songs from the Shaker Tradition

by James Slowiak with Alicja Ruczko

“These songs could be your life’s work.” Grotowski reached for his tobacco pouch to fill his ever- burning pipe. Or was it a cigarette he reached for? I don’t remember which he was smoking in June 1989 when he first witnessed my work with songs from the Shaker tradition in the Barn, the primary Objective Drama research facility on the campus of the University of California- Irvine. Certainly, he was smoking. We sat across from each other in the booth of a late-night restaurant—a rare thing in 1980’s Orange County. We often came here (was it a Bob’s Big Boy?), from 1983-1986, during Grotowski’s three-year residency at UC-Irvine before he moved his research center permanently to Italy. We came to this restaurant, or to other equally absurd and antiseptic California establishments, to analyze the day’s work and discuss the next steps. Now, we were talking about the new cycle of songs that I had introduced to participants during the first six months of 1989 when I led Objective Drama activities in Irvine.

After two and half years in Italy as one of Grotowski’s three assistants, I left his workcenter in Pontedera on New Year’s Day 1989, to return to California. My task was to select a group of UC-Irvine students and continue the activities of the Objective Drama Program in the USA. Grotowski planned to join me in Irvine for two weeks in June 1989 to witness and verify the work that I had accomplished. This project would conclude my six-year “apprenticeship” with Grotowski, before I embarked upon my independent career as a performance researcher, professor, and stage director at The University of Akron and as co-artistic director (with Jairo Cuesta) of New World Performance Laboratory (NWPL).

On the plane to California from Italy, I fretted about how to engage once more with American college students, especially concerning “traditional” songs, a major aspect of the practical activities of the Objective Drama Program. I didn’t feel comfortable introducing songs from the Afro-Caribbean tradition, which now formed the basis of Grotowski’s personal research, Art as Vehicle or Ritual Arts. As I gazed out the window of the airplane, I asked myself which songs most mattered to me from my own youth. I remembered learning the song, “Simple Gifts,” at a high school summer theatre camp. I knew that this popular folk song came from the Shaker tradition, and I wondered if there were a few other Shaker songs that I could teach to the students. I made a note to investigate Shaker songs at the UC-Irvine library. Remember, this was well before the internet, and information was not immediately available like it is today. I settled back in my seat, closed my eyes, and went to sleep, unaware for the moment of the grand adventure that awaited me.

Once I began to research material at the university library, I found not just a few songs, but a treasure trove of songs, hundreds, even thousands of songs. Many of these songs were “received” during moments of ecstatic possession or trance and, only later, written down as compositions. My curiosity was piqued. Who were the Shakers? From where did these songs come? And why did they create this extraordinary body of music?

WHO ARE THE SHAKERS?

The American Shakers, officially known as the United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing, emerged in the 18th century in England. The group migrated, soon after their founding, to the American colonies, arriving just in time for the Revolutionary War and the establishment of a new country. As avowed pacifists, the Shakers were persecuted initially and sometimes jailed for their beliefs. Soon, however, Shaker communities prospered and, eventually, flourished across the young country, most notably in New York, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and even as far west as Kentucky and Ohio. Today, only one community still operates in Sabbathday Lake, Maine.

The Shakers’ leader, Mother Ann Lee, whom they believed to be the second coming of Christ, founded the sect based on the principles of gender equality, pacifism, celibacy, communal living, and work as worship. Living in self-sustaining communal villages, the Shakers thrived through various industries, including farming, craftsmanship, and manufacturing. They developed a distinctive architecture and kept their buildings in good repair and spotlessly clean. Excelling in furniture-making, textiles, and agricultural inventions, Shaker products were known for their exceptional quality and attention to detail. The Shakers believed: Why wait for Paradise? Let’s create Paradise on Earth. Such conveniences as the circular saw, the clothespin, the washing machine, and seeds in packets were invented within Shaker communities and shared with the outside world.

The Shaker’s religious practices involved ecstatic worship, including vigorous dancing and singing, which they called laboring. On Sundays, people from “the world” would often attend Shaker services, like going to a theatre performance, to watch the intricate and finely coordinated group dances and physical movement and to appreciate the distinctive rhythmic vitality and beauty of the simple melodies. The songs, structured in a way that allows the entire community to participate in singing, use horizontal harmony or unison, as opposed to vertical harmony or polyphony, creating a sense of unity and egolessness. Shaker songs are rooted in the sect’s religious doctrine, many with lyrics that speak of universal themes like Mother, Father, Home, Journey or consisting solely of vibrational sounds. The intense and transformative experience of singing and dancing allowed the Shakers to enter a heightened state of awareness. New songs were often “delivered” when a member was in this heightened, “trance” state. The songs became an integral part of each member’s daily life and served various purposes within the community.

FUNCTIONS OF SHAKER SONGS WITHIN THE SHAKER COMMUNITY

The Sabbathday Lake Shakers, the only active Shaker community, maintain the heritage of Shaker music in the world today. The music remains accessible for researchers and artists from many styles of music. “The majority of Shaker songs originate from the mid-19th century and have been preserved by the Shakers through oral tradition. There were at one time in excess of 25,000 Shaker songs and, today, as many as 1,000 remain a part of the active repertoire of the Sabbathday Lake Shakers.” (hSps://www.maineshakers.com/music/) While the music provides a rich resource for today’s musicologists and artists, it’s important to understand how the songs function in the daily lives of Shakers, both in the past and today.

Firstly, Shaker songs functioned as an instrument to facilitate all kinds of creative expression. The Shakers believed that their songs were gifts from the divine, received by spiritual inspiration, not deliberately composed. By singing the songs, followers could channel and communicate with the spiritual realm. The songs acted as tools to deepen each person’s relationship with the sublime and foster a sense of spiritual communion within the group. In Grotowski’s lexicon, one might use the terms organon or yantra, precise instruments or tools that have an objective impact on the performer or doer. (Wolford 39-40)

Secondly, Shaker songs served as a powerful means of communication and a reservoir of cultural knowledge. As Shaker communities expanded and thrived, it became essential to transmit the beliefs and values of the sect to future generations. The medium of music proved to be a highly effective vehicle for this purpose. Shaker songs were not only sung during worship meetings but also throughout the day, during work, and on special occasions. Through the simple melodies and unornamented language of these many songs, the Shakers not only preserved their religious teachings, but also reinforced the sense of identity and unity of belief for those singing the songs. Their culture, their knowledge, is encoded in the songs.

In addition to their spiritual and instructional functions, Shaker songs played a crucial role in fostering a sense of community and connection among the believers. The Shakers followed a strict separation of genders in daily activities. Their buildings often displayed two entrances, one for men and one for women, with separate staircases inside, to prevent physical contact between genders. However, during worship services and gatherings, men and women would come together, forming a collective chorus. The shared experience of singing in unison created a sense of belonging and togetherness, breaking down the barriers of gender, ego, and individuality. The power of collective singing became a force that strengthened communal bonds through anonymity and promoted a sense of harmony through serving one another.

In conclusion, the power of Shaker songs lies in their multifaceted nature, serving as a means of creative expression and communication of cultural knowledge, and promoting a strong sense of community. These songs are not merely musical compositions; they represent a living tradition that spans generations and connects individuals across time and a variety of landscapes. The simplicity and purity of the melodies, lyrics, and rhythms evoke a sense of sacredness and unity that transcends time and space. What I discovered for myself in the UC-Irvine library was a cultural legacy; a cycle of songs that resonated through the ages, touched me deeply, comforted, inspired, and reminded me forcefully of the power of music as a tool for work on oneself. The Shaker songs provided me with the precise material I needed to begin work with Irvine students and the songs soon found their place in the activities of the Objective Drama Program. The Shaker songs, not only served as a tool of work in Objective Drama, but just as Grotowski had predicted, they became a field of performative research for me for the next thirty years.

INTRODUCING THE SHAKER SONGS IN IRVINE--1989

For several weeks, I immersed myself in everything I could find about the Shakers and their music. With the help of recordings, I began to learn several songs. I selected songs which steered clear of overt Christian references. Instead, the songs I chose mirrored many of the principles of the work in Objective Drama, as I understood them, and from my work with Grotowski in Italy, as well. A good example is the song, “The Happy Journey” (Andrews 99):

O the happy journey that we are pursuing,

Come brethren and sisters, let’s all strip to run.

These words describe Grotowski’s notion of the via negativa. In all aspects of the work, training, acting propositions, and singing, the students were asked to eliminate habits, strip away physical and psychological blocks, confront challenges. “The Happy Journey” reminds us of this principle. The song continues:

Let all be awakened and up and be doing

The exercises, besides singing and physical training, practiced in Objective Drama (i.e., The Motions, Watching, among others) were built over time as tools to increase one’s attention and stay “awake.” The reminder to “do” rather than “feel” or “be” served as a mantra for the young actors working in the Barn as they struggled to master Stanislavski’s system of psycho-physical actions and develop their craft.

That we may attain to our destined home.

What does it mean to arrive “home?” One goal, for theatre artists and for human beings, is to accomplish a more authentic self. “The Happy Journey” quickly became a kind of anthem for the practical work we were engaged in at the Barn.

I learned several songs myself. However, I also identified those students who had some musical abilities and assigned each of them a song to learn and, eventually, to teach to the rest of the group. In her book, Grotowski’s Objective Drama Research, Lisa Wolford describes how I first introduced the Shaker songs into the program of work at the Barn in 1989:

In early stages of the work, each participant was assigned to learn a number of songs from musical notation, then teach these orally to other members of the group. Once the words and melody of a song were learned, Slowiak guided us towards discovery of the song’s patterns of vibration and resonance, elements that cannot be conveyed by standard notation, and which we attempted to reconstruct (in a subjunctive, “as-if” mode) through a sort of “virtual archaeology,” a process of trial and error that continued until the energetic impact of the song seemed to have been realized. (Wolford 43)

As we worked technically on singing the songs, establishing the tone, melody, and rhythm, I also felt the need to explore how to move with the songs. There are no genuine Shaker dances in existence, only literary descriptions and several lithographs that visually depict groups of Shakers at a worship meetng in various formations moving through the space. In this case, we worked with Grotowski’s principle of meetng the song as a person and asking the song questions: Are you old or young? Are you a song of the field or the house? Are you a song of work or leisure? Lisa Wolford describes this process:

For each song integrated into the group's vocal training, a simple structure of movement was developed. This could involve a particular type of walking, running in a certain pattern, or even a simple swaying motion. These movement structures were not regarded as independent elements (i.e., dance or choreography), but rather were perceived to be in service to the song, aiding the actor to sing more freely. “First, you have to establish the song,” Slowiak instructed, “then allow the movement to grow out of that.” (Wolford 43)

The work with the Shaker songs in the Barn in 1989 proceeded almost magically. The Irvine student actors and other Objective Drama participants, like Lisa Wolford, Massoud Saidpour, and Jairo Cuesta, recognized immediately the richness of the material and its possibilities and everyone approached the research on the songs with seriousness and curiosity. In this way, we were able to progress very rapidly and very deeply.

Slowiak’s directive to “prepare for singing” was greeted with a particular sense of joy and excitement; at a certain point in the work session, it became clear that group members regarded the Shaker songs as our most valuable work. This was due in part to the creative dynamic that emerged between Slowiak and the group; it was freer and more vibrant in these songs than in any other aspect of our activity. Our encounter with the values encoded in the Shaker songs, such as simplicity, humility and impeccable attention to details of craft, provided us with a challenge that infused and richly inspired our way of working. (Wolford 43-44)

When Grotowski arrived in Irvine from Italy in June 1989, the group had an immense amount of material to demonstrate—physical and vocal training structures, The Motions, Watching, and two performance structures, one based on The Egyptian Book of the Dead and another based on Jaime De Angulo’s Indian Tales. Jairo Cuesta had also developed a new exercise called Four Corners. But the highlight of the demonstration, the main topic of the discussion between Grotowski and me that night at Bob’s Big Boy, was the work the group had accomplished with the Shaker songs.

The most exciting discovery of the work session, in Grotowski’s view, arrived by means of the student actors’ work with Shaker songs. Not only were these songs representative of our best creative effort, as we had managed in this instance to unite structure with life, but we had also unearthed an unexpected and precious treasure in terms of the songs themselves. Grotowski recognized and responded to the group's particular regard for these songs, which he attributed partly to Slowiak’s infectious love of the material. In addition, he acknowledged the value of these songs as traditional material, grown out of American soil and rooted in an Anglo-Protestant cultural heritage. Clearly the Shaker songs held rich potential in terms of yantra and organon. (Wolford 69)

Armed with this precious tool, I now felt ready to leave the master’s workspace. With Grotowski’s blessing, I began to look for jobs where I might be able to continue my research. Grotowski urged me to investigate the possibilities of university theatre programs. He felt that drama departments in US universities held the greatest potential and resources for theatre experimentation and research. (Grotowski 1995, 117-118) I accepted a position at The University of Akron, in Ohio, near where an important Shaker community had once thrived. Several participants of the 1989 Irvine session eventually joined me in Akron. This group, along with several University of Akron students, formed the basis of what would become New World Performance Laboratory (NWPL), the theatre company I co-direct with Jairo Cuesta.

FROM TRADITIONAL VOICES TO THE WATCHERS (1990-1992)

In fall 1989, I started my new position as Assistant Professor of Theatre at The University of Akron. I was hired to teach Acting, Voice, and Movement classes on the undergraduate and graduate levels and to direct one theatre production each year. It was a perfect position for me because I didn’t need to specialize in only one aspect of the actor’s work, but I could continue to investigate a more wholistic approach to performance training. I immediately began to introduce the Shaker material in both voice and movement classes. I also proposed a new class for the spring semester, Creating Performance, which would enable me to work more systematically with a group of interested students in building a performance structure with the Shaker songs. Grotowski was adamant, at the end of the 1989 Irvine session, that I needed to work the songs within a narrative framework. I found Nathaniel Hawthorne’s short story, “Feathertop,” which had already been dramatized several times. The story of the witch, Mother Rigby, who builds a scarecrow, gives him life, and sends him out into the world, fit very well with the songs and reminded me of the mythic material that I was accustomed to working with under Grotowski’s guidance.

In the beginning, I devoured all the information I could find about the Shakers and traveled to Shaker museums in New Hampshire and Kentucky and to the only existing Shaker community in Maine. I also found a great deal of primary material in the Western Reserve Historical Society in Cleveland. I was often amazed by the power of the songs to transform those singing them. Students who had little or no relationship with their bodies or voices would soon become more integrated, gain confidence and alignment, as they sang these songs over long periods in unison with others. Lisa Wolford observed the effect of the songs on me as leader/conductor during the 1990 Irvine work session with Grotowski, after I had already been working with the songs for more than one year.

Slowiak, who had been repeatedly urged by Grotowski during the previous year's session to take a more active role as leader/participant in the vocal work, engaged actively during early stages as conductor of the songs, assuming a peripheral role in the final structure. A recurrent highlight of our previous year's work had been a movement structure that accompanied “Shaker Life” in which Slowiak would dance in response to the singing of the chorus. While I am certain that the power of the Shaker songs as yantra/organon—a tool that has a direct impact on the energetic state of the doer— affects every participant to some degree, I have rarely witnessed a transformation so striking as Slowiak’s. It is as if some aspect of his personality, his constructed social self, visibly dissolves under the influence of the songs. His movement becomes freer and more vibrant, with an austerity that characterizes his social persona perceptibly lightening (both in the sense of radiance and transcending heaviness). (Wolford 77-78)

Using the “Feathertop” narrative as a framework and incorporating further exploration of movement patterns and spatial coordination exercises, as well as authentic Shaker texts, we eventually created a rough performance structure called Traditional Voices, that was performed one time only as part of the Cleveland Performance Art Festival at the Unitarian Church in Cleveland Heights, May 1990. I continued to work on the “Feathertop” material in conjunction with the Shaker songs in a two-week seminar in Irvine in June 1990, with Grotowski participating actively in the work sessions. Grotowski found the “Feathertop” material fascinating, and he took a great deal of pleasure in working several acting propositions with the students. Lisa Wolford describes the work during this session in detail in the chapter, “The 1990 Session: Headpiece Filled with Straw.” (Wolford 73-104)

In Akron, I explored the songs and performance structures with a select group of students. Raymond Bobgan and Massoud Saidpour joined Jairo Cuesta and me in Akron in 1990. Lisa Wolford arrived a bit later. Joseph Lavy and Zhenya Lavy (both Akron students at the time) were integral to this period of work. Zhenya assumed primary responsibility for conducting the songs and, together, she and Joe emerged as the natural leaders of the song cycle. The technical execution of the songs reached a high level during this period of work as well as other activities, such as physical training, Four Corners, Watching, and acting propositions. The “Feathertop” narrative was abandoned, and a story inspired more directly from the songs themselves and from Shaker journals and stories emerged. This new version of the Shaker song structure was performed in New York at La Mama Galleria in early 1991. When the Akron group (soon to be called New World Performance Laboratory) traveled to California for a six-week work session with Irvine students in Summer 1992, they were already operating as a strong ensemble.

The 1992 Irvine Session allowed us to work consistently for long periods of time without interruption. Holly Holsinger, an Irvine graduate student who had worked during all the California sessions since 1989, joined the core ensemble; as did Lisa Black, an Irvine graduate residing in Chicago, who had expressed interest in relocating to Akron. Besides these two, the core ensemble now consisted of Jairo Cuesta, Zhenya Lavy, Joseph Lavy, Massoud Saidpour, Raymond Bobgan, Lisa Wolford, Timothy Askew, Asha Soulsby, Mark Ross, and Claudia Tatinge. Two interns were also working with the company from Australia and Brazil.

Given the size of the group, we decided to experiment with the performance structure. I wanted to compare the energetic impact and transformative qualities of the Shaker songs with other American traditional folk songs of a more secular or profane nature. I divided the group in two—one group specialized in singing the Shaker songs and the other group developed a secular cycle of songs, including popular songs like “Careless Love” and “Skip to My Lou.” The narrative structure that appeared told the story of two groups occupying the same space—one, from the World, became intoxicated and reveled in their sensuality; the other, from a spiritual realm, sang and danced to transform themselves into more sublime beings. The Shaker group was eventually called The Watchers. They were invisible to all but one young woman from The World. The story became about her Calling and Initiation into the group of Watchers.

This structure was compelling, but unwieldly. However, it led us, along with a separate structure that I developed with the Irvine students, to discover the story for Mother’s Work, which would become NWPL’s major opus featuring the Shaker songs.

MOTHER’S WORK (1992-1994)

Upon NWPL’s return to Ohio in the fall of 1992, we began to work on the first part of the full- length performance, Mother’s Work. The Ancients involved the birth of a Messenger who was nurtured and educated by the elders and then sent on a journey to the World. The Ancients was performed at Cleveland Public Theatre in November 1992. Mother’s Work, which included Part 2, the Messenger’s journey through the Wilderness, and Part 3, the Messenger’s arrival to the World, premiered at the same venue in May 1993 and subsequently toured to Romania and Belgium. A second version of Mother’s Work was presented a year later at Oberlin College and the Festival Internacional de Londrina in Brazil. Critics responded to the company’s high level of craft, physical versatility, and the “simplicity and harmony” of the work. During this time, several long-time company members left NWPL, and new members arrived.

I realized during the presentations in Brazil that we had been putting too much attention on narrative structure and public performance of the material. In doing so, we had lost track of the most important aspect of the songs—singing them as a tool for personal transformation and seeking what Grotowski called “the secret of the song.” We had learned a lot about storytelling and working within a precise structure, but the power of the songs and their ability to work energetically on the performer had been diluted in the process. Part of the reason for this particular focus had been my own desire (and I think Grotowski’s, also) to distance the work from Grotowski’s ongoing research. When the Shakers experienced a period of high creativity and received an abundance of new songs, they closed their doors to spectators from the World and spent several years “laboring” in isolation. The longest of these periods became known as Mother’s Work. It’s from there we took the title of our performance. After performing Mother’s Work for more than two years, I now wanted to gather the songs we had been singing for the last five years and place them in a different context, far away from the public’s eye or any worry about narrative clarity for the performers. After our return from Brazil, Jairo and I went to Italy to begin a series of workshops in Performance Ecology. Most of these workshops took place internationally between 1994 and 2005, especially in Italy and Poland. The Shaker songs found their place naturally as a primary tool in NWPL’s Performance Ecology workshops.

ESSENTIAL DEMONSTRATIONS (1999) AND THE GILDIA RENDERING (2004)

Performance Ecology is Jairo Cuesta’s name for the program of research he has developed since his ten years of work collaborating with Jerzy Grotowski in Theatre of Sources and Objective Drama.

Performance Ecology focuses on the development and execution of non-narrative, nonverbal activities performed in adaptive relation to a given environment. The project strives to renew the participant’s awareness of a direct, immediate relation with the external world, a sensitivity to what Cuesta calls genius loci, the spirit of the place. Performance Ecology features physically intensive, structured activities that decenter the dominance of the internal discursive voice, enhance kinesthetic awareness, and render the participant more responsive to other means of communication—elements commonly imperceptible to urbanized individuals... (Wolford 148)

Although Lisa Wolford reports that NWPL’s development of the Shaker songs abruptly stopped after Mother’s Work, this was far from true. (Wolford 187-188) Within the context of Performance Ecology, the Shaker songs reached a new life and level of quality, and their significance to the company’s work became even more apparent. It was during this time also that NWPL began to explore more systematically the Solemn Songs, the earliest songs of the Shakers that were usually wordless and only involved sounds. The company’s approach to the Solemn Songs and their execution took on a simpler and lighter aspect that led to a new kind of relationship in the space with each other. Jairo and I called this new sense of play, “lila,” a term which we took from Stephen Nachmanovitch’s Prologue to his book, Free Play:

There is an old Sanskrit word, lîla, which means play. Richer than our word, it means divine play, the play of creation, destruction, and re-creation, the folding and unfolding of the cosmos. Lîla, free and deep, is both the delight and enjoyment of this moment, and the play of God. It also means love.

Lîla may be the simplest thing there is—spontaneous, childish, disarming. But as we grow and experience the complexities of life, it may also be the most difficult and hard- won achievement imaginable, and its coming to fruition is a kind of homecoming to our true selves. (Nachmanovitch 1)

To work practically on the idea of lîla, NWPL developed a group exercise called The Rendering. As director, I would organize the songs, dances, individual actions, and sometmes even group activities, like Watching or Four Corners, into a structured improvisation, with strict rules concerning adaptation, seeing, listening, and attention to the others. The main rule was to serve the others and to create the space and time for the others to do. The Rendering was primarily an exercise in craft.

Rendering ...is a slow search for the essential, for actions that are literal.

During The Rendering, the performers should not seek some kind of emotional or psychological self-expression. The goal is to see that life is neither this nor that: it just is. For those doing, The Rendering takes place in ecological time, eco-time, not ego time: the interaction of one’s whole being with the reality of here and now. What does it mean to be alive right now? To refuse numbness and security in favor of risk and immediacy? In The Rendering there is no place to hide. It is pure work. And this kind of work is part of the craft tradition; it is continuous with life. (Slowiak and Cuesta 162-163)

By incorporating the Shaker songs into The Rendering, NWPL arrived much closer, than in any of the previous performance structures, to discovering the “secret of the song,” uncovering its energetic impact, and understanding how these songs can function for us today. There were two major creative peaks in this period of work with the songs, both involved participants who worked with NWPL off and on over a period of several years. One group was primarily Italian and the other Polish. The Italian group presented their work for a small group of witnesses, after a four-week residency at The University of Akron in January 1999, under the name Essential Demonstrations. The Polish group, Gildia, presented their final rendering in 2003 in Olsztyn. Alicja Ruczko provides an excellent testimonial of how she and other members of the Gildia Project experienced the Shaker songs.

A TESTIMONIAL BY ALICJA RUCZKO

FIRST ENCOUNTER

I remember my first encounter with the Shaker songs. It was during the Gildia Project organized by the Tratwa Association in Olsztyn. The project was led by James Slowiak and Jairo Cuesta with a small group of young people, including myself. Jim taught us Shaker songs using a method of repeating phrases with great attention to the precision of sound and rhythm of each song. He emphasized the involvement of the entire body in singing, but without unnecessary movements. There was no room for improvisation or pseudo-artistic flights. The work was concrete and, one could say, artisanal at the beginning. Attention and presence were immensely important, and their absence, like an ultra-sensitive sensor, was immediately noticeable. The context of singing and the purity of intention in our work were also significant aspects I could sense. I remember that the first impression was very strong. By then, I was familiar with various songs, but I found it difficult to categorize the Shaker songs. They did not tell sad, tragic, or dramatic stories like traditional Polish or partisan songs, nor were they as grandiose as religious hymns or sentimental like sung poetry. I didn't find them fittng into any known category of songs. Some of the Shaker songs initially made me burst into laughter. I think it was a shocked reaction to encountering an unfamiliar musical form. Because my knowledge of the English language was very basic at the time, I often didn't understand what these songs were about. Many of them didn't contain words, only abstract expressions like "lo, lo" or "vum, ve, vum, vum". Now, after over twenty years of studying the vibration of the human voice and songs from various parts of the world, I see that it greatly helped me decode these songs using the proper key. Logic of the mind was deactivated, and it became a pure experience of sound vibration through the physical body and feeling them in the space of the heart. By saying "feeling in the space of the heart," I mean experiencing the subtle qualities of vibrational frequencies while singing the Shaker songs.

The hours of physical work led by Jairo Cuesta preceding the singing, which awakened the body from its mechanical functioning, as well as the work with mindfulness, activated organic energy flows throughout my being. This multidimensional process of awakening the body prepared it to experience the songs at a much deeper level than the ordinary singing I had known until then. The impression was striking! After each singing session, I felt that something extraordinary was happening on many levels.

SONGS AS AN ENERGETIC CODE

On a physical level, I began to observe that my whole body vibrated long after singing. It was a fascinating experience. After each session of singing Shaker songs, I distinctly felt a physical expansion at the top of my head. I remember this didn't happen during voice work, such as exercises and improvisations. Interestingly, I could sing them for hours while maintaining a high level of mindfulness. Very vivid and symbolic dreams also appeared. Another observation I made on a physical level was a sense of lightness, illumination, and a feeling of floating.

Once I mastered the basic level of the songs, including the melody, text, and rhythm, the songs started "flowing" through my body in vibrational streams, causing specific emotional states and influencing my well-being. I began to experience the different qualities of each song, which they carried within them. The sensations were usually uplifting, associated with opening the space for empathy, joy, harmony, or touching the sphere of spirituality in its purest form. I also observed a certain clarity and lucidity of the mind.

I now know that songs of such quality operate as energetic codes. When we fully engage in the act of singing, these songs influence our body and hormonal system, creating a very precise state. This state encompasses physical, emotional, and energetic experiences.

A TOOL FOR SELF-WORK AND BUILDING RELATIONSHIPS

The process of singing Shaker songs, which took place over several hours, occurred at an individual and group level. The feelings and states that the songs evoked in us began to affect the relationships within the group. A community was born, and even though we didn't fully understand what was happening, the relationships between us started to clear. Everything that was concealed began to come to the surface, as if the truth started to penetrate the layer of falsehood built from our daily roles and masks. It was not an easy process, but incredibly transformative. It allowed me to experience relational truth in the community we became during the project.

SONG AS VIBRATIONAL INFORMATION

When we start to sing a song, its energetic code becomes active, along with its message. The song flows through our fiber-optic cable, which is our body-instrument. The more unobstructed the fiber-optic cable, the better the conduction and the more readable the message. The intention with which the song is called to life also plays a crucial role. If we do not take responsibility for our intentions, the song can "carry us away" or lead us to a more or less aesthetic musical form that may be empty in its vibrational message.

In conclusion, in my opinion, the greatest value of the Shaker songs is the awakening of the body to its own organic nature, the unblocking of energetic flows, and the activation of specific vibrational codes within the body. With the benefit of hindsight, I also see that these songs anchor certain qualities in individuals: sensitivity towards others, acting with the heart, simplicity, surrender, and responsibility.

I have observed that during the singing of some Shaker songs, the vibrational qualities not only enhance the individual’s singing but also effect sensitive listeners. In a colloquial sense, if these songs are sung in the right conditions, they harmonize and uplift us. They become a kind of vibrational medicine, serving as subtle tools that support well-being and human development. Shaker songs are my guides and close friends; they are precious gems that illuminate the person singing and his/her surroundings.

CONCLUSION

Grotowski was right. These songs became my life’s work. Since 2003, the songs have served less as a tool of work and more as a precious gift, like the family’s china that gets taken out when guests arrive for dinner. Each member of NWPL keeps a special relationship with the songs that they hold close to them in whatever kind of work they are doing. Other theatre companies have recently utilized the Shaker material to create productions, including The Wooster Group and Martha Clarke. These attempts were, for the most part, about searching for some kind of historical re-creation of how the Shakers may have presented their songs and dances. NWPL’s work with the songs never looked for any kind of imitation or historical accuracy. Our work has always been about meeting—meeting the songs, meeting each other, and meeting ourselves. I summed up my own relationship with the Shaker songs in an interview with Lisa Wolford:

Slowiak himself is aware of the magnitude of his transformation when working with the Shaker material. “I know that when I work with these songs,” he said to me in a later conversation, “I can tap into the creative self, the ‘little i.’” The distinction he makes between “Great I” and “little i” is based on the lyrics of a Shaker song. “Little i” is the humble self that subjugates ego before the needs of the community. Self-exalting “Great I,” the egocentric social self, stifles the possibility for creative work and can be redeemed only when one becomes aware of and submits to “little i” (connoting humility and conscious acceptance of discipline rather than infantilism). (Wolford 77-78)

Great I, little i Great I can see Little i is simple i, so little i will be.

Little i is simple i And little i is free Little i is simple i, so little I will be.

As a Shaker sister exclaimed when she heard this song: “Well, that says it all, doesn’t it?” (Patterson 216)

Note: Patterson uses the word “pretty” instead of “simple.” NWPL sings “simple” based on our own research and understanding of the song.

Here is a link to a different Shaker song:

WORKS CITED

Andrews, Edward Deming (1940) The Gift to be Simple: Songs, Dances and Rituals of theAmerican Shakers. New York: Dover Publications, Inc.

Grotowski, Jerzy (1995) “From the Theatre Company to Art as Vehicle,” contained in Richards, Thomas (1995) At Work with Grotowski on Physical Actions. London: Routledge.

Nachmanovitch, Stephen (1990) Free Play: Improvisation in Life and Art. New York: Tarcher/Putnam.

Patterson, Daniel W. (2000) The Shaker Spiritual (2nd Edition). New York: Dover Publications.

Slowiak, James and Cuesta, Jairo (2018) Jerzy Grotowski (2nd Edition). Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

Wolford, Lisa (1996) Grotowski’s Objective Drama Research. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

ILLUSTRATIONS

Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library. "[Shaker dancing]" The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1830 - 1839. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/cdbb9320-07c4-0133-27ff-58d385a7b928

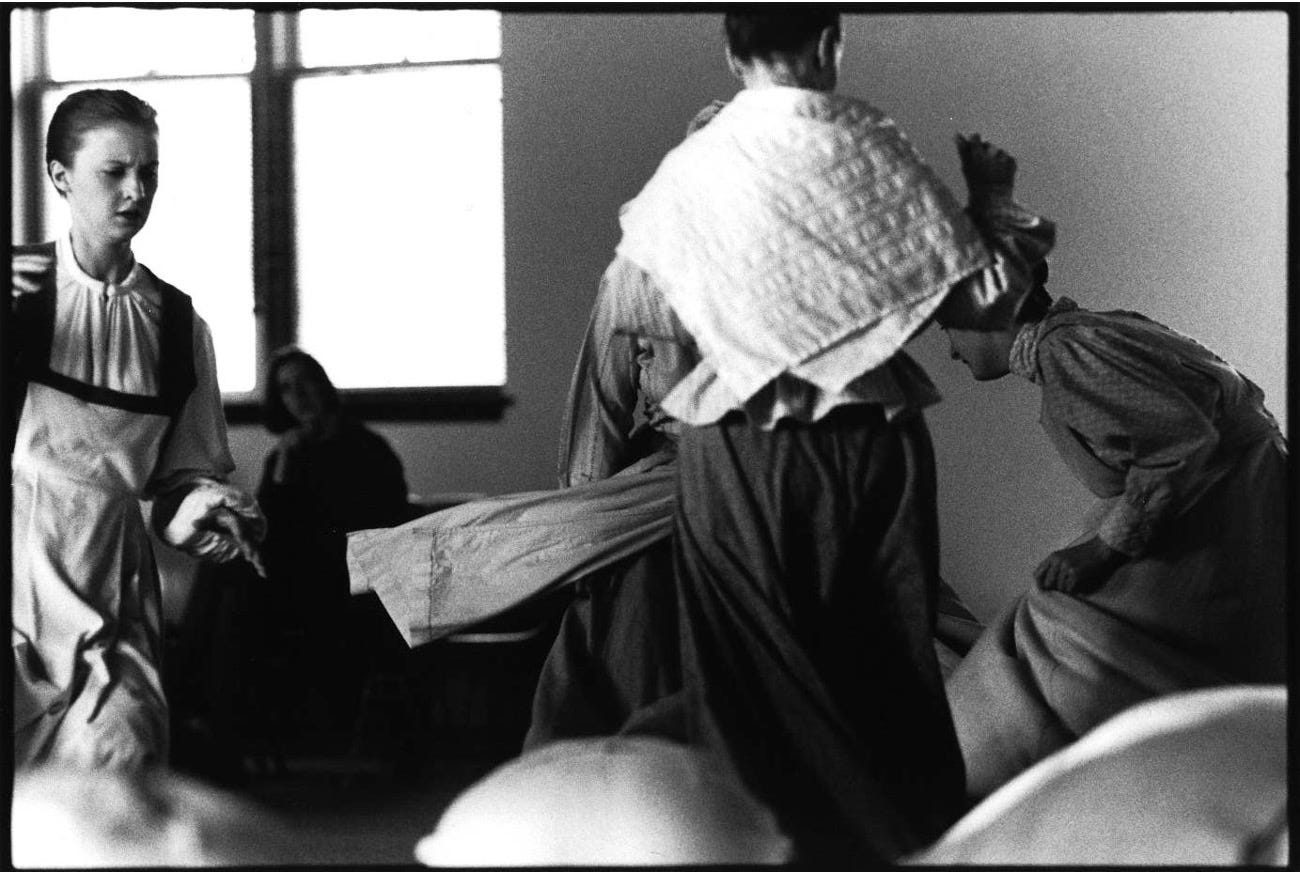

Traditional Voices, presented as part of the Cleveland Performance Art Festival 1990. Photo by Thomas Mulready. From NWPL Archives.

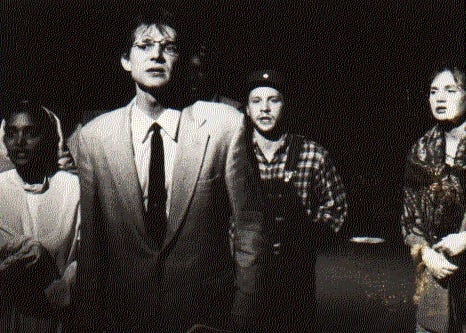

The Ancients, presented at Cleveland Public Theatre, Fall 1992. Photo by Robert Schnellbacher. From NWPL Archives.

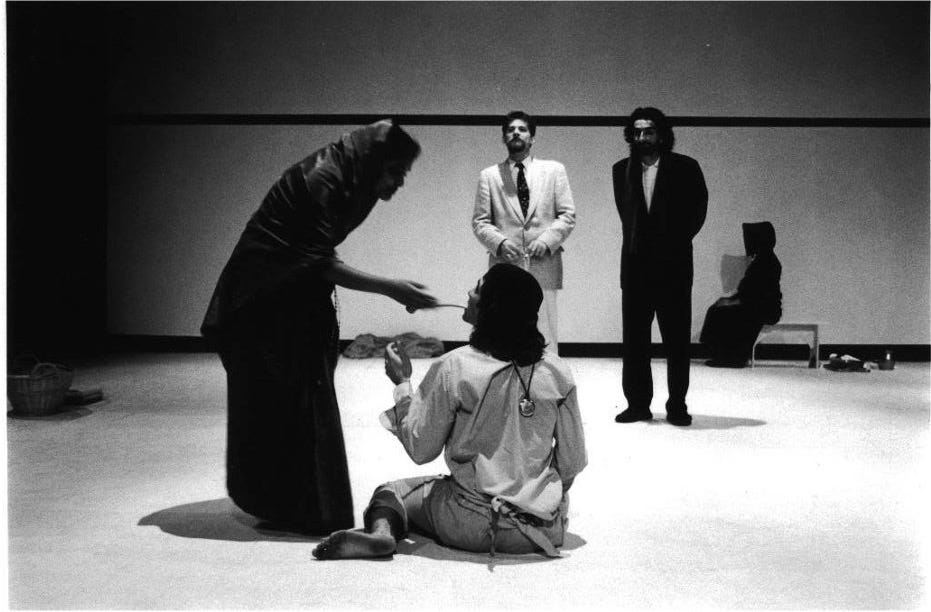

Mother’s Work (Version 1), presented at Cleveland Public Theatre, Spring 1993. Photo by Douglas-Scott Goheen. From NWPL Archives.

Mother’s Work (Version 1), presented at Cleveland Public Theatre, Spring 1993. Photo by Douglas-Scott Goheen. From NWPL Archives.

The Gildia Project Rendering, presented in Olzstyn, Poland, Summer 2002. Photo by Douglas-Scott Goheen. From NWPL Archives.

The Gildia Project Rendering, presented in Olzstyn, Poland, Summer 2002. Photo by Douglas-Scott Goheen. From NWPL Archives.

The Gildia Project Rendering, presented in Olzstyn, Poland, Summer 2002. Photo by Douglas-Scott Goheen. From NWPL Archives.

How amazing! I really appreciated readng about the path of your life's work and the Shaker Tradition.