Memories...(not the Cats kind, although one does get mentioned)

Jim's Musings from Paris June 2024

This week has been all about remembering—remembering good times with friends from Ohio and Minnesota—but, most of all, remembering the immense sacrifice that was made on the beaches and in the fields, villages, and cities of Normandy 80 years ago. The numbers have been repeated often and we have seen the images of the rows of white crosses and watched, while munching popcorn, Steven Spielberg’s graphic depiction of events in his film, Saving Private Ryan. For years, the dignitaries, tourists, and survivors have made the pilgrimage to Normandy so that we have become almost immune to the bloody massacre that occurred on Omaha Beach and elsewhere on D-Day and in the harrowing days which followed—USA 29,000 killed, UK 11,000, Canada 5,000. Sometimes we forget the thousands of French civilians who were also killed by Allied bombs and Nazi retaliation (12,200) and the German soldiers (30,000), occupying a land that was not theirs and indoctrinated in a cause based on a flagrant disregard for the essential human values of dignity, diversity, liberty, and compassion. Of course, these numbers, taken from Britannica.com, are just estimates. The exact number of casualties associated with D-Day will never be known. Just as the exact number of casualties from the wars in Ukraine and Gaza will never be known. Beneath the rubble of human aggression lie many corpses.

I recently posted a quotation of Maria Montessori on my Facebook page. She talks about the fact that our childhood education is based on learning how to compete against each other, how to overcome the other, how to make war. She wonders what would happen if we taught our children how to cooperate, to offer solidarity, to make peace. I wonder this, too.

Last Thursday, we attended the batizado (baptism) of Léo and his best buddy, Milo, as they received their new belts in their capoeira class. Capoeira is a martial art, dance, and art form, that traces its origins to the African continent and was elaborated and practiced (often in secrecy) in the northeast of Brazil (about 400 years ago) within the enslaved communities. Capoeira combines kicks, escapes, take-downs, and acrobatics with a unique musical aspect, incorporating singing, clapping, drumming, and the playing of several musical instruments. The resulting demonstration, usually performed in a circle, displays an hypnotic style and thrilling creative expression. During the batizado, the initiate who is progressing to the next level has to demonstrate his/her knowledge of the physical skills learned, as well as songs and rhythms. Léo and Milo each had to face several different instructors, work with other students, and teach their parents (and one abuelo) some of the movements and songs.

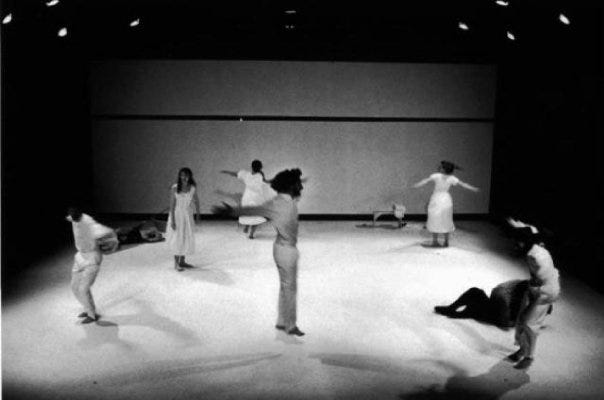

I first encountered capoeira when New World Performance Laboratory was invited to perform its production of Mother’s Work at the Festival Internacional de Londrina (FILO) in Brazil in 1994. We were hosted by the festival for almost two weeks, gave four performances, conducted several workshops and work demonstrations, saw almost all the other guest performers, and had several important cultural meetings: one with a lyalorixá (a Candomblé priestess) and the other in a capoeira dojo where the NWPL members were able to participate in a master class. As I sat in a corner of the gymnasium watching Léo the other day, I was reminded of that night in Brazil, thirty years ago, when I watched a very international, eclectic, and diverse group of actors based in Akron, Ohio, fearlessly plunge themselves into what was then a relatively unknown martial art in the USA.

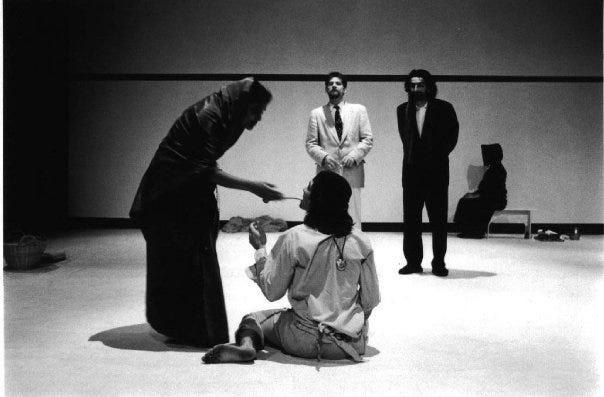

That particular group of actors was especially fearless. Many of them had joined Jairo and me two years earlier, in summer 1992, at UC-Irvine, for one month of intensive work in the Barn and the Yurt, the facilities of Grotowski’s Objective Drama Program, where we demonstrated an early version of Mother’s Work and other Performance Ecology exercises and performance structures to Grotowski himself. Most of those actors then traveled with Mother’s Work one year later, in 1993, to the theatre festival in Piatra Neamt and other cities in Romania, just four years after the fall of Ceaucescu. We performed our Shaker opus, along with The Recital of the Bird, based on Avicenna’s poem, adapted and directed by NWPL member, Massoud Saidpour, at the famed Bulandra Theatre in Bucharest, sang Shaker songs in the mountain monasteries, and shocked the Romanian audiences with our impeccably rendered message of simplicity and craft.

Yes, the NWPL actors were fearless and they were welcomed unconditionally that warm night in Londrina. As I watched them struggle with the unfamiliar movements and rhythms from my obscure corner of the dojo, I understood first hand that capoeira had evolved from an aggressive martial art, practiced for survival, into a tool for physical, spiritual, and community development. Now, thirty years later, I saw once again first hand as I watched Léo in the rondo (circle) with his teachers, friends, and their families, that capoeira is a game, “played with a partner, not fought against an enemy.” Perhaps capoeira can be one of the tools used to teach peace that Maria Montessori yearned for? But does it go far enough?

Transferring the lessons learned in the dojo to the real world can be difficult. Teaching peace does not happen naturally in our culture. After the baptizado, I accompanied Jairo and Léo to the park and playground near Léo’s house. Here, I was confronted suddenly with a microcosm of the actual world with all of its petty hostilities, violent confrontations, prejudices, and self-protectionist tendencies. I watched with horror as allegiances formed and exploded, risks were taken, property was confiscated and destroyed, insults hurled.

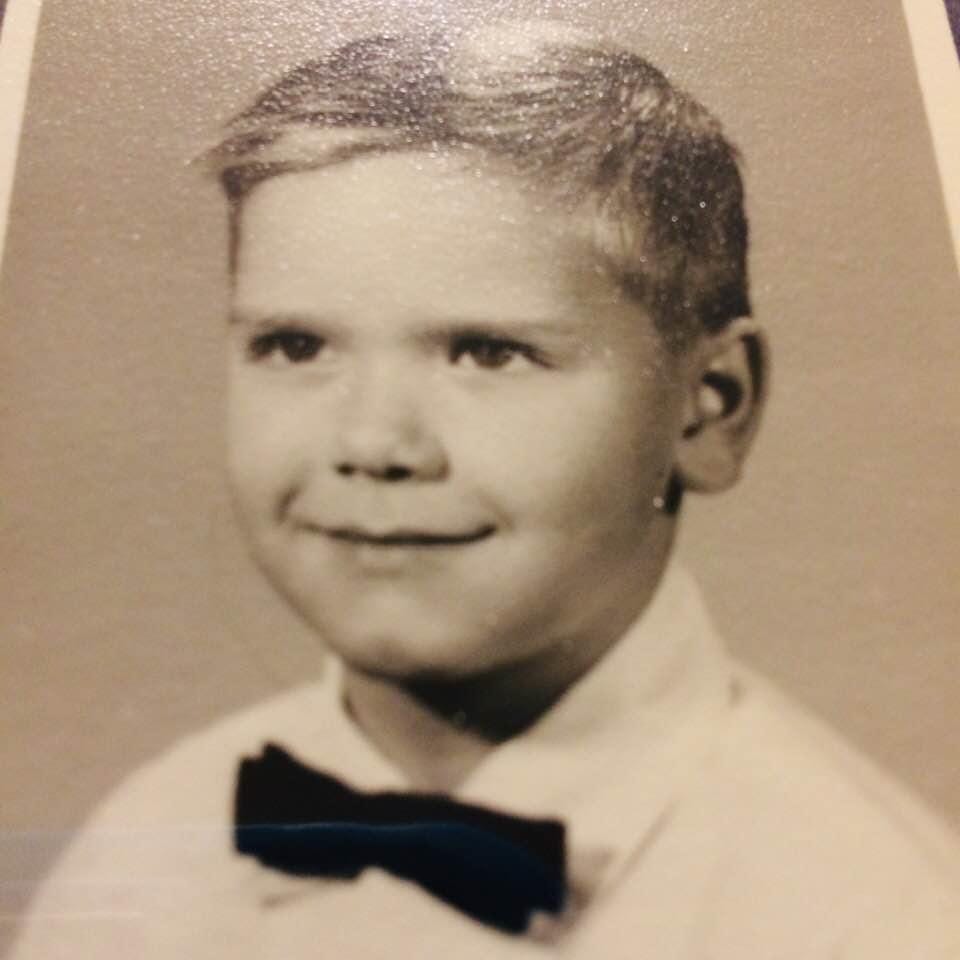

All the inherent cruelty of the playground came rushing back to me. I remembered my own misadventures on the playground in kindergarten. One day I was chased around the outside of the school building, Lincoln School, in Stanley, Wisconsin. In one direction all the boys in my class ran after me—to beat me up. In the other direction, all the girls in the class chased me—to kiss me. I could only escape by running into the building where a parent-teacher meeting was being held. My mother was always the youngest, the prettiest, the most elegant and best-dressed of all the mothers. I was sure she would defend me. All the mothers and the teacher, Mrs. Brown, sat in a circle in our classroom. I ran to my mother, breathless and in a panic. She held me at arm’s length and laughed at me when I tried to tell her what was happening outside. She brushed me off, embarrassed by my behavior, and told me to get back to the playground. Of course, by the time I got back outside, everyone was already absorbed in another activity. Just like the actual world, priorities had changed, life had moved on.

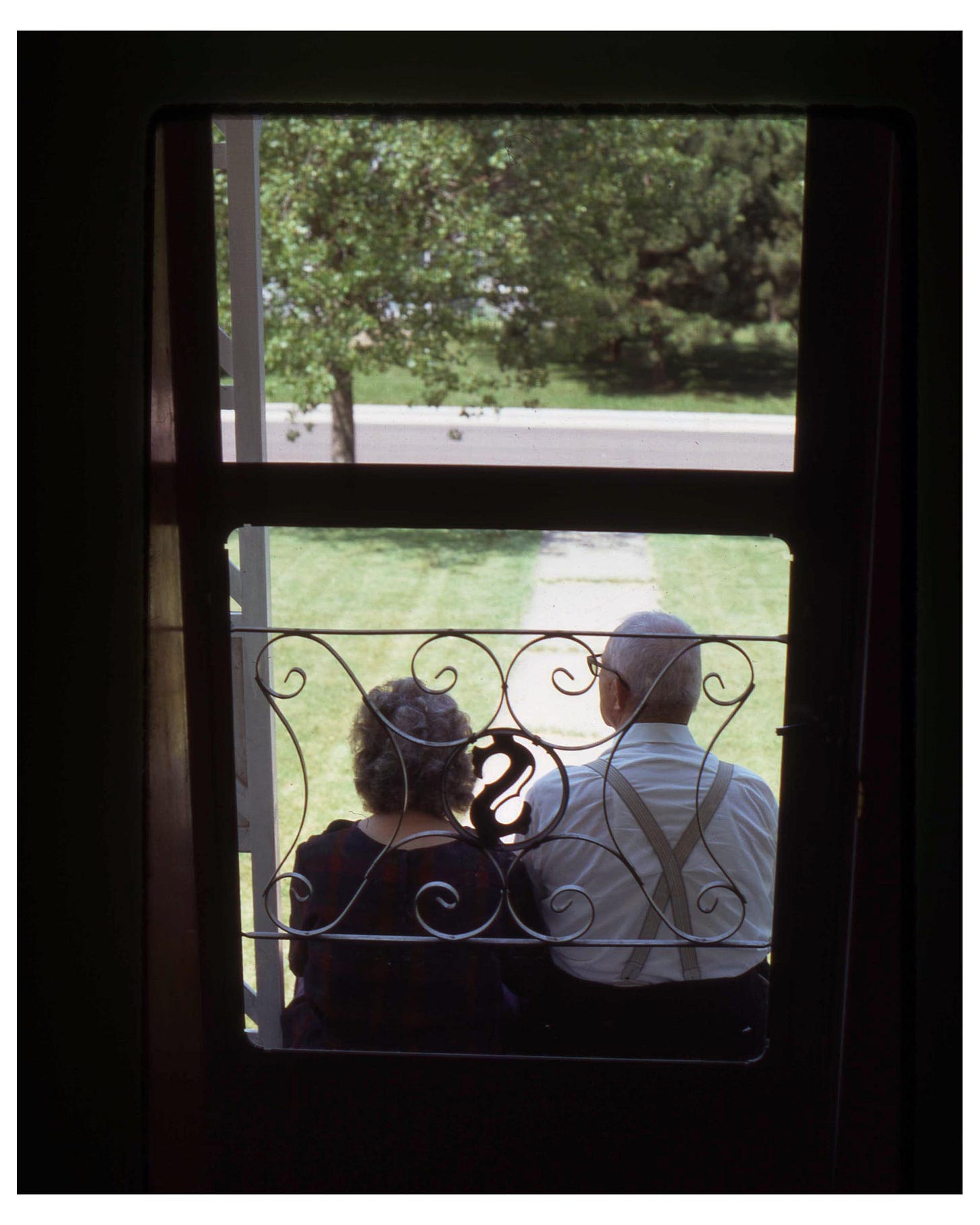

There was also the time I was walking to my Grandma Slowiak’s house after school. It was only a few short blocks. About two blocks from the school, I ran into a group of boys—kids from my class and older kids from the neighborhood—maybe five or six of them. I asked them what they were doing. They said they were waiting for me. When I asked them why, they said, “Cuz we’re gonna beat you up!” And they all jumped on me. Somehow I got myself out from under the pile-up and ran as fast as I could to my grandmother’s house. As the group of boys sauntered up the street to the front of her house looking for me, my Polish grandmother walked out on her front stoop, shaking her wooden spoon, naming each of them, and telling them to “get home right now and leave Jimmy alone.” I wasn’t hurt badly, but she tended to my wounds. I loved my Polish grandparents. They couldn’t give us as many material gifts as my mother’s parents, but I felt safe in their house and I have strong memories of security playing cards at the kitchen table with my grandpa and snuggling in the featherbed in their guest room each morning, after my mom dropped me off, before I had to go to afternoon kindergarten.

Life on the playground in those years in Stanley was rough. We would have rock fights where we would actually throw stones (large stones) at each other. There was one kid who tortured cats. And other kids who smelled badly or whose ears would spontaneously bleed, who now I can see were clearly suffering from abuse at home. When I got to first grade and Catholic school, my playground misadventures became much less violent. I became more of a leader, I guess. But those early years marked me emotionally and physically.

I wish I could save Léo from the realities of the playground. I wish there was some special place where he could play without having to deal with the jealousies, cruelties, and stupidities of others, but as I write this newsletter the extreme right has “won” the European elections here in France with over 30% of the vote. French President Macron has just dissolved parliament and called for new elections at the end of this month! In three weeks!

Playground politics continue in the real world with all of its dangers and absurdities. I hope that those who died 80 years ago to liberate France will not have died in vain. Take the memory of them to the ballot box with you, my French comrades. May democracy prevail and not allow itself to be beaten once again by tyranny.

More to come…

What a beautiful interweaving of the personal and the political. But looking at that photo of little Jimmy makes me think he might have been a handful.